Spoilers for Inside follow

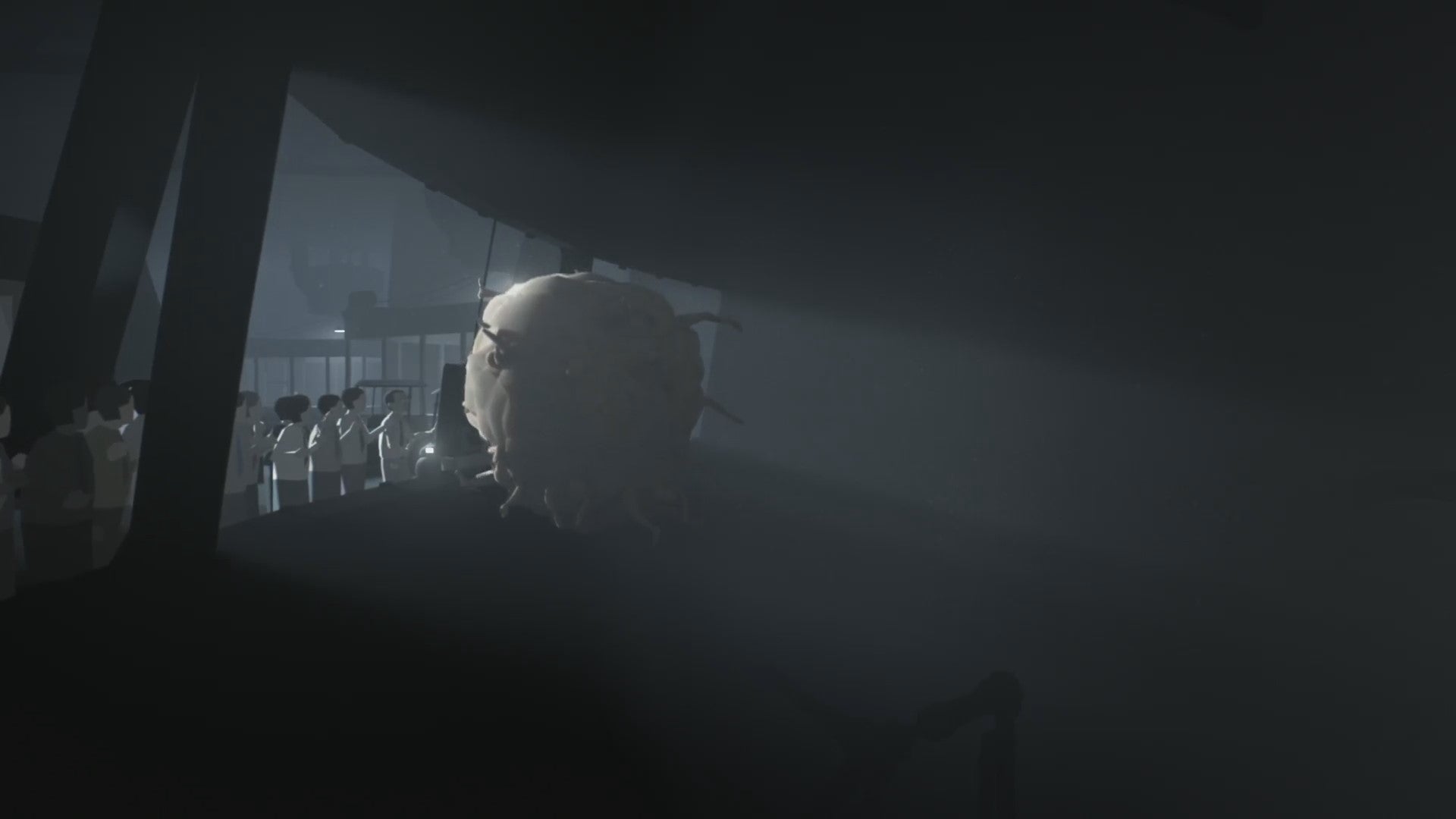

When Inside came out, at the time I hadn’t played Playdead’s previous title Limbo, though I was familiar enough with it that I more-or-less knew what I was in for. Both games are puzzle platformers, with a young, silent protagonist whose journey is just as much a mystery to them as it is to you. The world of Inside is an alluring one. There are quite clearly some fascistic undertones to the world, with much of the masses seemingly indoctrinated into following… something. You yourself are forced into controlling select groups of the population, commanding them in ways that allow you to advance through the various puzzles the world places before you. It is, quite obviously, a game about control and authoritarianism. So where do you and the young boy you play as come into it? Your role is that of the controller – pardon the pun – leading the faceless lad into the unknown. The world becomes a little more fleshed out as you progress, but you never learn anything significant about how things came to be as they are, or who the boy even is. You discover one thing about him though: his purpose. Which is, for reasons that the game refuses to be clear on, become a part of what you could reductively call The Blob (or would more specifically call ‘a mass of human flesh and limbs’). For ease of discussion, we’ll go with the first one for the rest of this article. The Blob is the boy, and the boy is The Blob, and you are the boy, all meshed together in a way that feels very reminiscent of the incredibly fleshy Society from 1989. As I mentioned earlier, I have played games that make me squirm in the moment. Inside is one of them – particularly during one section that shows far too many dead and rotting pigs. The Blob is the thing that sticks with me to do this day, though. I often like to describe my gender as an amorphous blob, almost unknowable, which might be why I’m so fascinated with this sentient, faceless creature. But its existence also strikes a guttural fear in me like not much else. It clearly has desires, like we all do, its main one being freedom. Scientists have trapped it, you see, and you as the boy are, as it is revealed in the end, on a quest to free it. Why that’s so, I don’t know. Is The Blob controlling the boy, and in turn you as the player, in order to free itself? Are the scientists encouraging it to do so? I can’t answer either of these questions, and that’s part of why The Blob is permanently etched into my brain (living rent free, I might add). The first time I played the game, I did so in one sitting, as it is quite short, and I almost think that’s part of the point: when I reached the point where you become one with The Blob, my partner and I – who was watching me play – were stunned. I’d started playing it quite late in the night, and obviously finished even later than that, and just didn’t know how to feel. For me, that was mostly because there was seemingly no resolution for The Blob. You do eventually escape the facility you were trapped in, but when you manage to do so, you and The Blob find yourself at a shoreline with nowhere to go. The world, after all, only moves in two directions, left or right. The ending implies freedom, but it doesn’t really offer it, either for The Blob, or for me or you as players. We are simply stuck together as the credits roll, doomed to be stuck in this one spot, maybe forever. That’s the thing that makes me uncomfortable. It’s not particularly obvious how the developers feel about The Blob, though I do think they’re sympathetic to its existence. I do think its body is something that is used slightly for shock value (which has troubling connotations) but I do also think there is a strong criticism in how those with power treat those who are even remotely different. So for this creature, or person, or sentient being, whatever it might be, the way we leave it makes me desperately sad, frustrated, and to hammer it home one last time, uncomfortable. Horror is at its best when it is trying to reflect something about the world around us. It is easily the most contemporary of genres at any given moment, always having something to say about the now. The best horrors are able to say something about the moment they were made in, but still feel timeless, even if it’s unfortunate when they are so. Inside is as powerful now as it was when it was released eight years ago, and I hope I’ve made it obvious how deeply affecting it is. Conveniently, it just so happened to have recently joined PS Plus, and while I may have spoiled what lies ahead of you, experiencing the game as a moving, visual piece will convey all of this better than I possibly could. Of course while I rarely need an excuse to consume anything horror-related, the approach of Hallow’s Eve certainly makes it an appropriate time to engage with that which bumps in the night. So do yourself a favour, and play the game with The Blob that will stay with you forever.